by: Hans Ralf Caspary Moreno

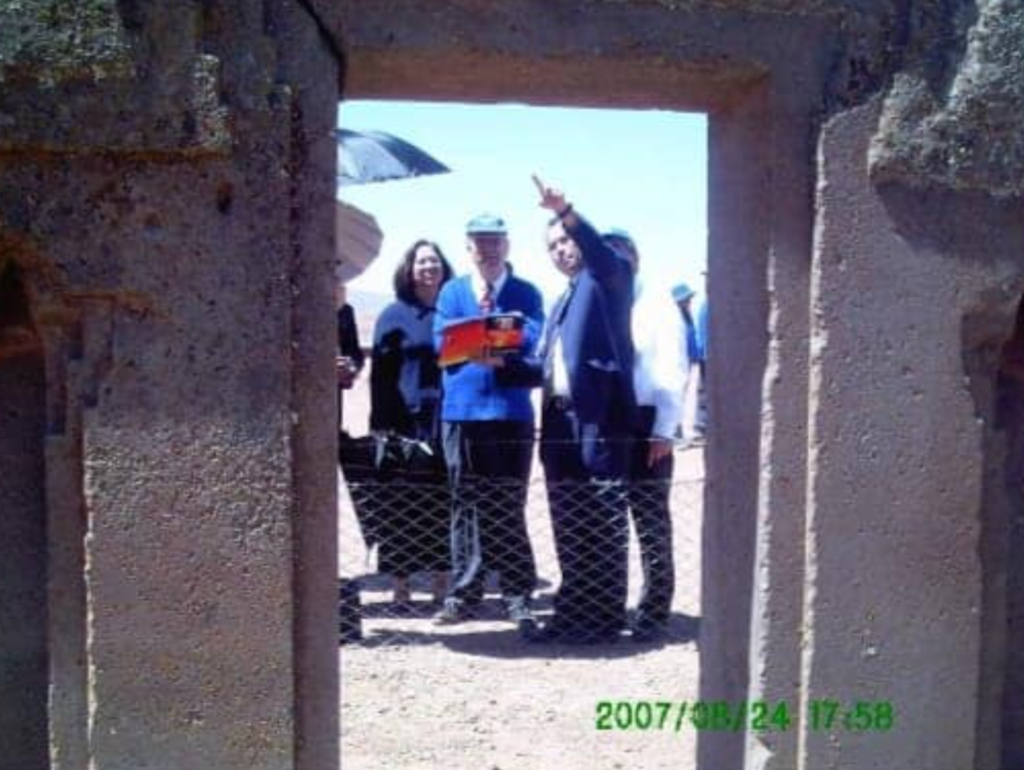

(Hans Caspary explaining to Elder Russell M. Nelson the symbolism of the Gate of the Sun located northwest of the Kalasasaya Temple in the ruins of Tiwanaku, August 24, 2007)

“Since time immemorial, it has drawn the attention of those who passed through this enigmatic pre-Hispanic city. The first European to set foot in Tiwanaku, which centuries earlier had been a sacred place, was the chronicler Pedro Cieza de León (1549). When he saw it, he was impressed and exclaimed: ‘Tiaguanaco is not a very large town, but it is renowned for its great buildings, which are certainly remarkable and worth seeing.’ (Pedro Cieza de León, Chronicle of Peru, Chapter CV).”

Later, driven by curiosity, he wanted to know the age of that city, and by asking the locals, he wrote: ‘I asked the natives… if the buildings had been made during the time of the Incas, and laughing at this question, they affirmed… that they had been built before the Incas reigned, but they could not say by whom it was done, only that they had heard from their ancestors that what we see was made in a single night.’

Thus, Cieza de León knew for certain that another civilization prior to the Incas had built that city with singular mastery, whose remains were already exposed on the surface of the Altiplano. The chronicler recorded this in writing and informed the viceroyal authorities in Peru, based in Lima, about the existence of these ruins.

I imagine Pedro Cieza de León, realizing that with the little he saw, it was enough to recognize that those who built the city were a highly advanced people compared to the Incas. He realized this by observing the way the stone was cut and polished, which were part of the buildings he saw crumbled before him.

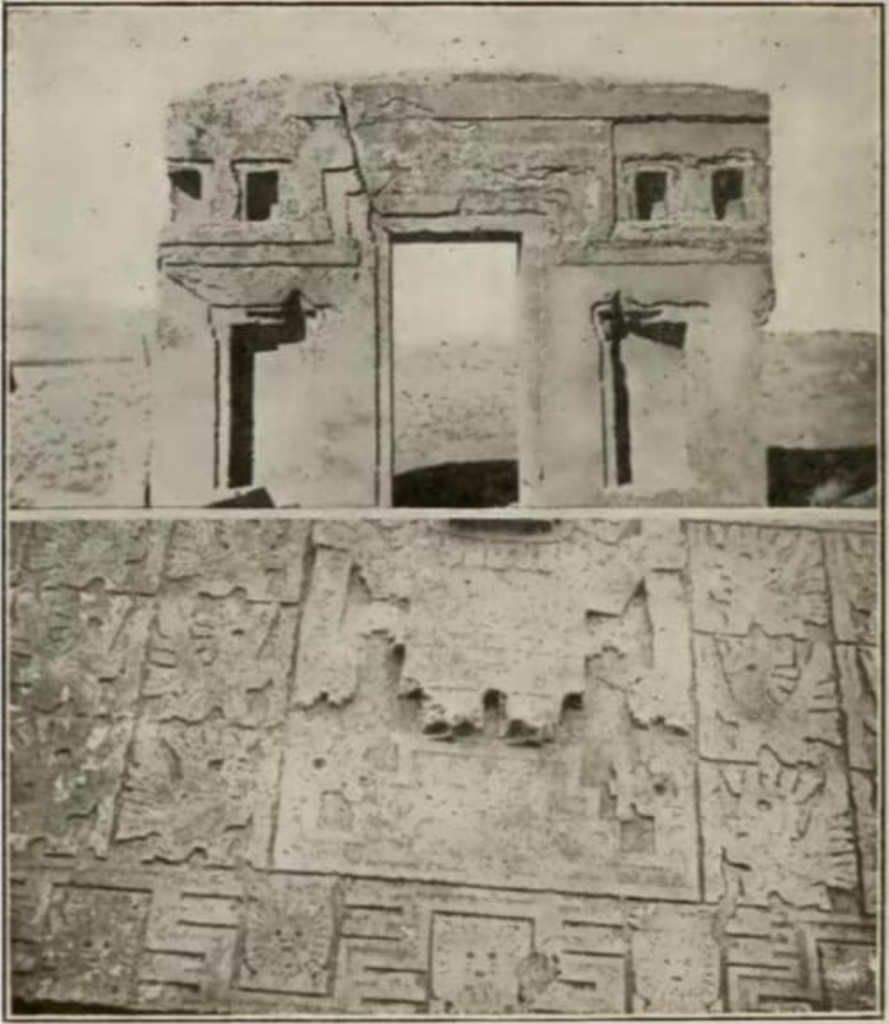

(Collection of old photos of La Paz by Marie Amirandar. 1890. In which the scattered remains of the Kalasasaya Temple in Tiwanaku can be seen.)

“Surely, what Pedro Cieza’s eyes saw was something similar to the scene observed in the photograph above.

From that point on, many others visited this place, and like Cieza de León, they were amazed by what they saw. Surely, they must have wondered: if what they were observing was in ruins and still a marvel, what must this city have looked like in its prime, during its peak of cultural splendor?

In 1995, Carlos Ponce Sanginés published his book Tiwanaku, 200 años de Investigaciones arqueológicas (Tiwanaku, 200 Years of Archaeological Research), in which he provides a historical analysis of the visits made to this archaeological site by important figures throughout the 19th century. One particular visitor that caught our attention was George Squier (1821–1888), an American diplomat, journalist, and researcher who visited Tiwanaku for two weeks in 1877. He dedicated many pages to describing what he saw, saying, ‘…I must say, having carefully considered my words, that nowhere have I seen stones more precisely cut, or crafted with greater skill, than those at Tiwanaku. No part of Peru contains anything that surpasses the stones scattered across the plains of Tiwanaku… The ruins of Tiwanaku have been considered by all observant and scholarly men, in regard to ancient Americans and in many other respects, the most interesting and important; at the same time, the most enigmatic on the continent. They have aroused admiration and wonder.’

Now, why do we mention Squier? Because this same individual appears in an article written by Fannie B. Ward in The Herald, Salt Lake City, on July 15, 1890. The article by this journalist describes Squier’s 1877 journey to Tiwanaku, offering new elements that we consider extremely important for us, the South American Latter-day Saints. Ward mentions that Squier compared Tiwanaku to the ‘Baalbek of America.’ Referring to the Kalasasaya temple, Squier said, ‘Those ancient architects, whoever they may have been, seem to have not understood the use of mortar, or perhaps they didn’t need it, being able to build so well without it. Like Solomon’s Temple, the stones were made to fit perfectly together.’ In other words, Squier noticed at a glance that the Kalasasaya temple had an architectural resemblance to Solomon’s Temple.

From Ward’s article, we can establish a historically significant fact for us, the Bolivian Latter-day Saints: members of the Church in Salt Lake City were aware of the existence of an archaeological site in South America, which among its remnants, housed a temple whose architectural form was very similar to Solomon’s Temple. At that time, The Herald was widely read in Salt Lake City, being considered the most important newspaper.”

“Surely this fact motivated many Church leaders to become aware of these ruins, and driven by curiosity, they wanted to visit them. In the early decades of the 20th century, a significant event occurred that marked the fulfillment of the prophecies of the Book of Mormon: the time would come when the true Restored Gospel of Jesus Christ would be brought to the remnant of Laman and Lemuel. This happened when Elders Melvin J. Ballard (of the Quorum of the Twelve) and Rey L. Pratt (of the Seventy), commissioned by the First Presidency of the Church, offered the dedicatory prayer for the preaching of the Gospel in South America. This prayer was offered in a park in Buenos Aires, Argentina, on December 25, 1925.

After this event, in July 1927, Elders Ballard and Pratt headed to Peru, with a mandatory stop in Bolivia, and decided to visit the ruins of Tiwanaku. It is logical to assume that they first passed through the city of La Paz, and from there, they gathered information on how to reach the ruins. Time and again, I have wondered why they chose to visit the ruins of Tiwanaku. What motivated them? Why didn’t they just continue on to Peru? The answer I can give is that before they came to South America, they already knew about these ruins and longed to see with their own eyes the temple that Squier visited in 1877 and that Ward wrote about in The Herald in Salt Lake City, describing the existence of a temple similar to Solomon’s.

Later, upon returning to Salt Lake City, Elder Ballard wrote a book mentioning his visit to Tiwanaku, dedicating 15 pages to his adventure. In his memoirs, he said, ‘I wish to describe some of the ruins we visited in three different places on this Andean plateau. First, in Tiahuanaco… I will only write about three points of interest. There are many more, as this was a vast city covering hundreds of acres of land. The first thing that caught our attention is known as the site of the Temple of the Sun. It is located on approximately ten or twelve acres and is completely surrounded by large carved monoliths.’ He was referring to the Kalasasaya temple, and when he saw the so-called Gate of the Sun, which is located northwest of this temple, he said, ‘…When we saw these symbols on the temple wall, we were deeply impressed that those who built it knew of Solomon’s Temple. Reading in the Book of Mormon that they built temples after the pattern of Solomon’s Temple, it is undeniable that these ruins belonged to the people described in the Book of Mormon.’ (2 Nephi 5:16. Italics added by the author of this article).

(Ancient Ruin of South America: Some External Evidence Supporting the Story of The Book of Mormon. Published by The Improvement Era magazine, Vol. 30, No. 11, September 1927. Published by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, pp. 960–973. Translated by José Luis Diaz Veliz).

As they toured and admired the remains of these ruins, Elders Ballard and Pratt were photographed beside the remnants of what may have been Nephi’s temple.”

(A surprising image in Egyptian style. Image number 5)

(Above: Image number 1. The stone gate.

Below: Interior of the Great Gate. Number 2)

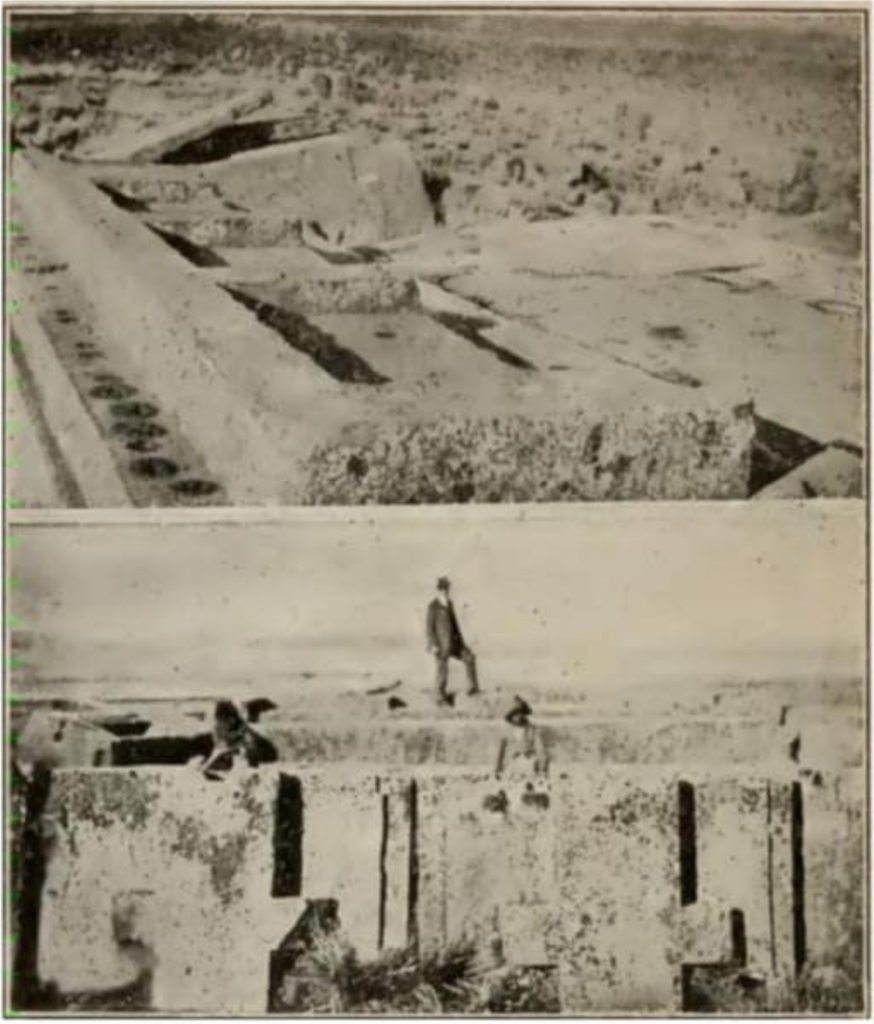

(Above: Frontal stone of the Temple. Image number 8. Below: Temple wall. Number 9)

(Carved monoliths around the Temple of the Sun. Number 3.)

“When we refer to the information provided by the Book of Mormon in 2 Nephi 5:16: ‘And I, Nephi, built a temple; and I constructed it after the manner of the temple of Solomon, except it was not built of so many precious things, for they were not to be found in the land, therefore it could not be built like Solomon’s temple. But the manner of the construction was like unto the temple of Solomon; and the workmanship thereof was exceedingly fine.’ In this scripture, Nephi clearly emphasizes the name of Solomon three times, and I believe he does this to stress that the design was inspired by the temple from the land they came from, ‘Jerusalem.’

Without fear of being wrong, I believe that if Pedro Cieza de León had had the opportunity to read the Book of Mormon in 1549, when he saw the ruins of Tiwanaku (Kalasasaya temple), he would have expressed the same thing as Squier (1877), and Ballard and Pratt (1926).

(Digital reconstruction of the architectural design of King Solomon’s temple)”

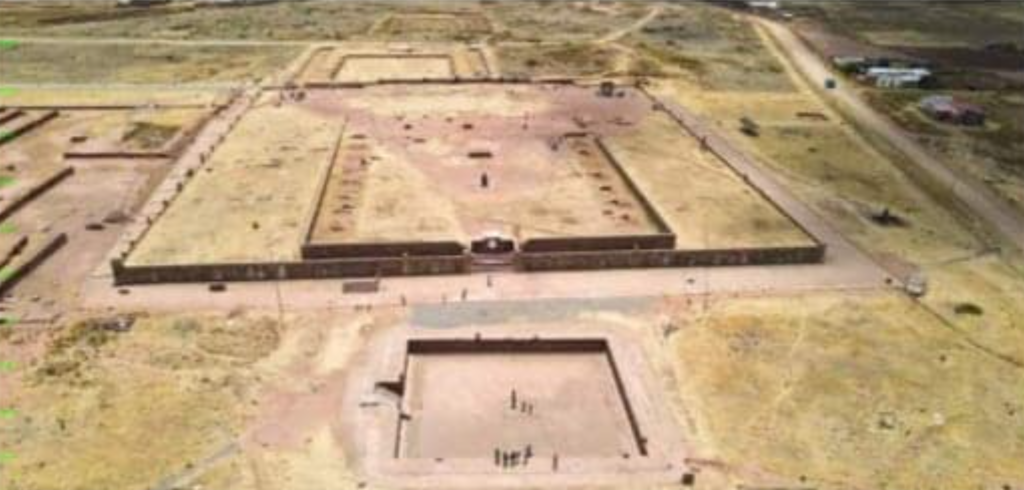

Aerial view of the east side of the Kalasasaya Temple

(Ideal reconstruction of the temples of Solomon and Kalasasaya)

I ask myself a question, which is: How should we, as Latter-day Saints, begin to view these ruins and their temple? I can respond by saying that we should view Tiwanaku as the possible city of Nephi and the Kalasasaya temple as Nephi’s temple.

In all of the Americas, there is no archaeological site with as many similar characteristics to Solomon’s temple. Perhaps someone might think that these characteristics are mere coincidences, but we could respond by saying that these are the best coincidences to continue comparing.

To gain a deeper understanding of the comparisons between the Kalasasaya temple and Solomon’s temple, you can look for the nine articles summarizing my latest book, The Kalasasaya Temple in the Ruins of Tiwanaku: Was It Nephi’s Temple?, which you will find on the Facebook page of the South Americanist School of Latter-day Saints in the Geography of the Book of Mormon group.

Note: I would like to thank Brother José Luis Diaz Veloz (Arica, Chile), a researcher and historian from the Church in Arica, Chile, for his valuable assistance with the historical data found in the Church History Department and for the translations he made from English to Spanish.

Full Article translated from Spanish to English by L. Enrique Meneses II